Workplace techniques of labor extraction as well as internalized notions of time-discipline have worked in tandem to set productivity as the default measurement of accomplishment. The drive for personal productivity as a burden inherited from colonial-capitalist notions of time and labor extraction manifest in external as well as self-monitoring and regulation techniques of the workplace. For some, this makes workplace surveillance and productivity monitoring something virtuous; it helps creates a feeling of getting a lot done

as well as the the satisfaction of knowing you worked really hard and it was measured.

As Melissa Gregg, the author of Counterproductive: Time Management in the Knowledge Economy, informs us, the quest for increased personal productivity—for making the best possible use of your limited time—seeks the pleasure of time management, which is ultimately the pleasure of control.

23 Having ingested the rhetoric, surveillance becomes a morality device tracking industriousness. It helps workers prove how good they really were.

24

In modern work culture, the worker and the workplace act in concert to undertake the colonization of the self by internalizing capitalist ideas of productivity and efficiency.

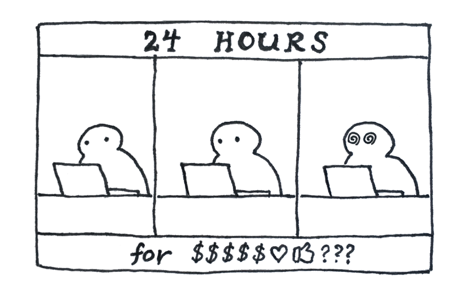

25 This is premised on the idea that we should consider life an economic venture: a race with winners and losers. This model of labor capitulates to a dissolution of boundaries where there are no longer 8 hours of work [perhaps there never were] but rather 24 potentially monetizable hours.

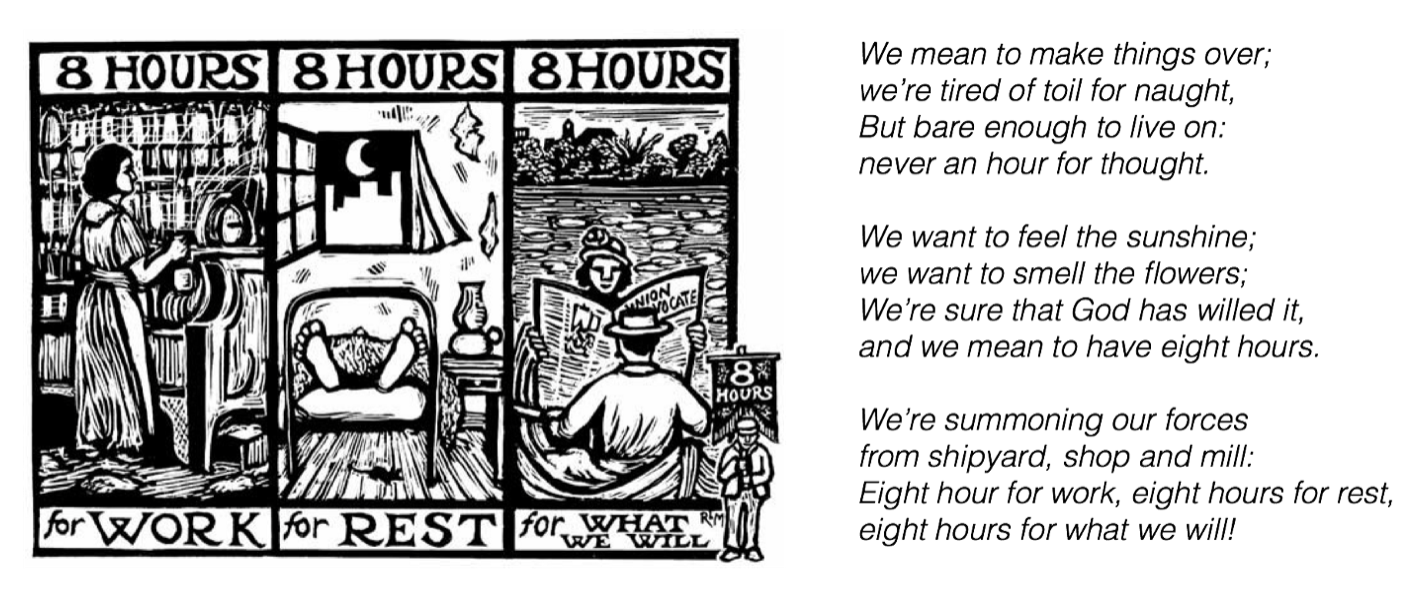

26 In the late nineteenth century, labor unions fighting for the standardization of the workday argued to establish 8 hours of work, 8 hours of rest, and 8 hours of what we will.

Technological connectivity has, troublingly, harmed this demarcation of time by creating an expectation of constant connection that does not leave room for any kind of silence or interiority.27 As work-from-home mechanisms installed by the pandemic have demonstrated, the blurring of temporal and spatial boundaries has done damage to the semiotic borders we draw between our work and non-work selves.

As part of this externally imposed and internally projected efficiency-based attitude, we have started feeling pressured to use our leisure time productively

too. Rest and recreation seem valuable insofar as they serve some other end, such as recuperating to do more work.28 Once our notion of time has collapsed into 24 monetizable hours, Jenny Odell argues, Time becomes an economic resource that we can no longer justify spending on 'nothing'.

23 Gregg, The Productivity Obsession.

24 Barbaro, The Rise of Workplace Surveillance.

25 Odell, how to do nothing.

26 Odell, how to do nothing.

27 Odell, how to do nothing.

28 Burkeman, Time Management