The power of the internet must certainly be that anyone can create a signal. Anyone, that is, with a caveat: Anyone with resources, a little technical knowledge, and access to infrastructures already in place. The global internet is a network made up of hardware including routers, servers, cables, satellites and devices like smartphones and computers. Access is normally dependent on commercial Internet Service Providers (ISPs). It can, for different reasons, prove to be unreliable, unattainable, or completely absent. It can be expensive or under prioritized in certain neighborhoods. Nationwide internet shutdowns can be imposed as a response to protests, as dissent on and off the internet is often made governable through weaponization of internet access. Otherwise, the necessary infrastructure to create a signal might be missing altogether.

While there might not be a single, centralized plug to pull to shut the internet down, it isn't necessarily a distributed network either. From the wires and cables to the governments making the laws, the internet implicates us in a system in which we are dependent on others, who are often more powerful than ourselves, to be granted access. Governments now create national intranets (local and internal networks cut off from the global internet), and online space is increasingly dominated by a few corporations through moderation, regulation and surveillance.2 These circumstances of relative centralization of the network itself make citizens vulnerable to having internet access and data transmission weaponized against them.

Scholar of media infrastructure Brian Larkin points out that “the weakness of technology is that as it becomes familiar, its scale is reduced and the feeling of the sublime dissipates”.3 In this sense, demystifying a governing technology becomes a political project. To Larkin, the sublime of technology has been used as a governing affect, to reinstate the power of the state, mainly under colonial rule. There are parallels between the sublime of colonial modernity and the technological sublime of the internet. The internet's sublime might feel like a vertigo. This vertigo, which the internet's intangible limitlessness provokes, along with the relative obscurity of its workings, can be understood as two sides of the same coin. Because, as Brian Larkin suggests, not knowing how a large system, technology or infrastructure works infuses it with a kind of power that can be used for governance and control, and might even make it seem more powerful than what it is. But rather than getting stuck on the application level, to demystify the internet, we would need to trace back through the backlog of hardware as well as the socio-technical dealings of states and legislative bodies to ask: how do you create a signal?

Larkin understands “signal” to mean “the capacity of media technologies to carry messages”.4 Network technologies can carry messages between users, even when they are not connected to the global internet. To create a signal in this context would mean to be able to transmit messaging or data on a network. The Internet is just one kind of network through which this can be done. The technology used to create the network we know as the global Internet - with its specific protocol, the World Wide Web - can just as well be used to create other separate and independent networks, intranets that are able to connect users to each other and distribute data. They can be national or local, connecting just a handful users, or a whole country.

Just as governments can create their own intranets, so can citizens. The present condition of the internet might be defined by the relatively recent emergence of microgrids, but the history of technological subversion is present in our culture already. An example is how commonplace piracy became in the early 2000's (more on that later). In this regard, Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) have an interesting genealogy. They can be used both for now-illegal data transmission and file sharing, as well as for bypassing internet filtration. However, they only work if you already have internet access.5 If you cannot use a VPN because of a total state initiated internet black out, mesh networks can operate locally without access to the global internet, making it possible to connect people on the same network, if you are within line of sight. In the case of national internet restrictions, mesh networks are technically able to distribute internet access, given that it can connect to a cell tower across the border, or a satellite in the sky.6 But in both these cases it would be necessary to already have a SIM card working with the cell phone tower operator, or have a modem compatible with the satellite, as well as that the satellite is providing connectivity in your geographic area.7 To connect to the global internet you are, evidently, always reliant on some of the hardware for telecommunication already in place.

Anthropologist Joanne Randa Nucho uses the notion of a 'post-grid imaginary' to describe the dissolution with the modern project, in regards to the electric grid.8 The infrastructural modern project converged with the emergence of the type of modern state power we know today. Between 1850 to 1960 Western cities in particular were transformed through big investments in the standardization and universalization of infrastructures like sewers and power lines, and interconnecting networks like the telephone. This was accompanied by ideals of interconnectivity, efficiency and rationality: the infrastructural ideal of modernity. Along with advent technologies concepts of time and space were reconfigured through the massively greater scope of infrastructures. The electric grid came with the promise of universal access to electricity and a widening state power.9 But Nucho describes how, in some places like Lebanon, it was never fully realized, forcing citizens to rely on generators. Contrast that with Northern California, and its functional grid: nevertheless there is a tendency now among affluent Californians to install their own generators in order to go off-grid. Nucho argues that these two very different circumstances both exemplify what she calls a “post-grid imaginary”: a dissolution with the modern project at large.10 The global internet can seem to be weighted with a similar kind of promise of universal connectivity, and the need to bypass internet access limitations might speak of a “post-grid” condition of the internet as well. VPNs and mesh networks can both be understood as microgrids, which, like electrical generators in Northern California and Lebanon alike, challenge the centralized nature of an internet connection. But contrary to the electrical grid, the internet implicates us in a system in which we are dependent on others, who are often more powerful than ourselves, to be granted access.

The internet is a more distributed kind of structure compared to the electrical grid, but it still maps itself onto the territories put in place by the modern project, in the same way as the electrical grid, serving to cement the territory of the nation by connecting it.11 Meanwhile, the internet makes social relations measurable, traceable and quantifiable,12 and so, by understanding the internet as a frontier to be conquered by being mapped, controlled and governed, it is possible to draw parallels between it and colonial paradigms. Infrastructures link space and citizens within the nation state, and are in themselves also a territorializing force.13 Today, the territorialization taking place on the internet works through the perception of online space as virgin lands, where resources in the form of data points are extracted,14 and where the cyberspace of the nation state tightens. Similar to colonized lands, the city in modernity was treated as “terra nullius,” or no man's-land, a frontier that had to be conquered and regulated.15 But space and place is, as history shows us, most of the time already somebody's land - and data is already someone's, independent of which server it might be sitting on. The post-grid condition of the internet itself, similarly to that of the electrical grid, is tied to the construction of the nation state and other governing infrastructures, as evident in national data protection regulations and nationwide internet restrictions.

To be able to transmit data is often crucial for social and political movements. Data can of course be transmitted offline, too. The informal term “Sneakernet” was popularized in the early era of the internet to describe data transmission in its simplest form: physically transporting data from a recipient to a receiver - by walking in your sneakers (or, perhaps, sneaking the USB into your sneakers to hide it)16.

Impactful decisions are often made within large corporations, rather than through democratic processes, leaving very little space left for citizens to interfere in decisions.20

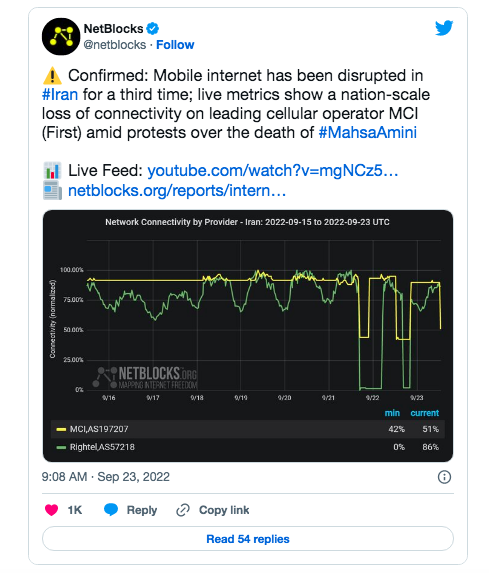

In the case of data protection, the border between data extraction and data exfiltration blur, and actual national borders play a crucial part. Several governments work together with corporations to create their own national intranets to have unfiltered access to citizen data. These intranets are networks, often in the form of superapps. Superapps are applications that offer many of the functions and services that are to be found on the global internet and that still function in the case of a state initiated internet black out, so as to nudge and push people onto these local apps and services that the government can surveil and control. In this way, governments move data traffic to their own networks. They connect the country internally but disconnect it from the rest of the world by filtering or entirely obstructing access to the global internet. National intranets are often filtered to account for critical media, for example. In the case of a nation-wide shutdown, they will still be functional, meaning that the only possibility for online communication maintained is a surveilled one. This is most recently seen in Iran, with the murder of 22-year old Jina Amini (a.k.a. Mahsa Amini) in September 2022 that sparked massive nationwide protests. In retaliation, the Iranian government repeatedly shut the internet down to prevent protestors from communicating and organizing. Many of these shutdowns were reported by Netblocks, an independent internet monitoring service, as the result of a loss of connectivity from the largest national mobile operators. This implies the ISPs collaborated with the government to cut their services.22

Similarly to China, with its superapps Baidu and WeChat, Iran evidently deploys strategies to create a national intranet. Ironically, it is often Western democracies selling these technologies to Non-western governments, where they are used to control dissidents. Belarus and Uzbekistan, to name a few, have acquired American technologies used to censor the internet.24

Superapps, adhering to data localization laws, make sure data is stored locally. These laws regulate where data is stored, and many countries' data localization laws state that their citizens' data should be stored in, as well as subjected to, processes adhering to the laws of the country it originated from. This includes, for example, China's Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which was passed last year. Similarly to the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the PIPL attempts to protect citizens from private corporations accessing their data. However, unlike the GDPR, it does not protect citizens from state authorities doing so.25 Interestingly, the U.S. Patriot Act, passed right after 9/11, does not protect U.S. citizens from having their data accessed by the government either, as long as the data is stored on American land.26 Data localization might be a seemingly reasonable measure to take to protect citizens, but it can also put citizens at risk. The stakes of each nation state vary according to localized interests, some of which are commercial, others repressive and even violent in nature. If advertisers and brokers can extract data, authorities can exfiltrate it, which policing bodies in both China and the U.S. have been known to do.27 During the Black Lives Matter protests in the U.S., law enforcement did just that in order to surveil protestors,28 and the U.S. military has been documented buying location data from apps to target certain demographic groups.29 As a consequence of data localization rules, in Russia, the Russian government demanded that the encrypted communications app Telegram store their data on servers within Russian borders. In practice, this means that authorities will be able to access Telegram's encryption keys.30

Although only little more than half of the world's population is connected to the internet,31 those of us that have access are still under the impression that it is globally ubiquitous. That this is a false assumption is apparent in the case of internet shutdowns during uprisings. The need to bypass internet restrictions might speak of a post-grid condition of the internet itself, similar to that of the electric grid, where its universal claim of connectivity is failing. But what really sets the internet apart as a different kind of grid than the modernist electrical grid is that an internet connection presupposes electricity and not vice versa; unlike electricity, water, food or fuel, an internet connection cannot be stored. 87 percent of the world's population have access to electricity, but only 63 percent have access to a stable internet connection.32 This necessitates certain conditions for the politics of internet access.

The nature of most internet microgrids suggests that the only way to counter internet restrictions in this case is to create and claim your connection yourself, rather than disguise it. These technologies only allow for a fraction of connectivity for what is needed, but this may be just enough to broadcast politically important material to the global web. Consequently, they are not large scale solutions; rather, they are small, distributed actions of resistance. As a result, microgrids of resistance can point us towards not only the weakest points of the internet but the weakest points in governing infrastructures altogether. What is at stake when you can or cannot connect to a satellite? The difference between the electrical grid and the internet is that having your own functioning generator is a much simpler project than creating your own internet access. Furthermore, the incentives seen globally to tighten national cyberspace might very well be understood as part of the same imaginary as the resistance it provokes. Microgrids and alternative infrastructures for digital communication can be understood as a sign of disillusionment towards the unitary ideal of the modern project, as technologies are constitutive of the paradigms they serve. As a kind of governing technology, the Internet is no exception.